Ypres Trip 2025

The Belgium trip is a once in a lifetime opportunity for me.

The Belgium trip is a once in a lifetime opportunity for me.

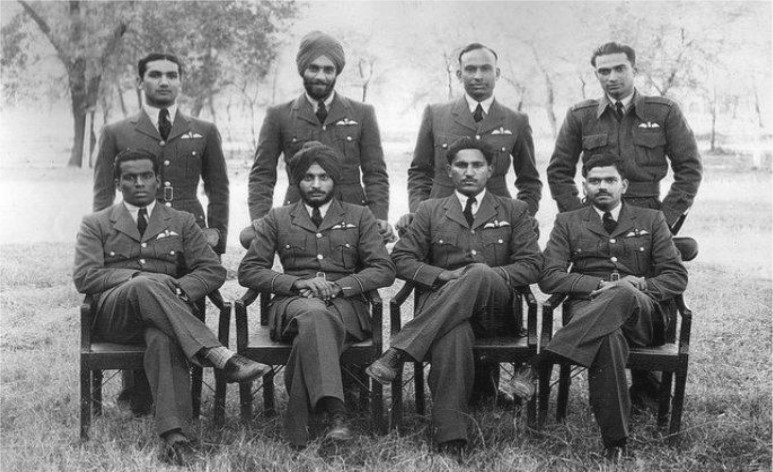

The contribution of nations within the British Empire was immense, and it is now generally accepted that without it, Britain would have found the conflict more difficult.

The contribution of nations within the British Empire was immense, and it is now generally accepted that without it, Britain would have found the conflict more difficult.

Thursday the 8th of May marks the 80th anniversary of VE (Victory in Europe) Day.

On Friday 8th November, I had the amazing opportunity to go to Ypres in Belgium, following on from what we have been learning about in history - The First World War. The journey to Belgium was an adventure in itself. It was very early, but spirits were high. We started with an hour-long coach journey to Dover to catch a ferry to Dunkirk. The ferry was a fun start to the day with a very yummy breakfast.

We travelled by coach to Ypres and explored many parts of the beautiful city. It was absolutely stunning, with its beautiful mediaeval architecture and rich history. The atmosphere was so vibrant yet peaceful and the local café and chocolate shops added to its charm. I was captivated by the Menin Gate, which holds such significant meaning as it is inscribed with the names of nearly 55,000 soldiers who did not return to their homes. It helps us to remember those who fought for their countries during the war. It was amazing to see what Ypres had to offer.

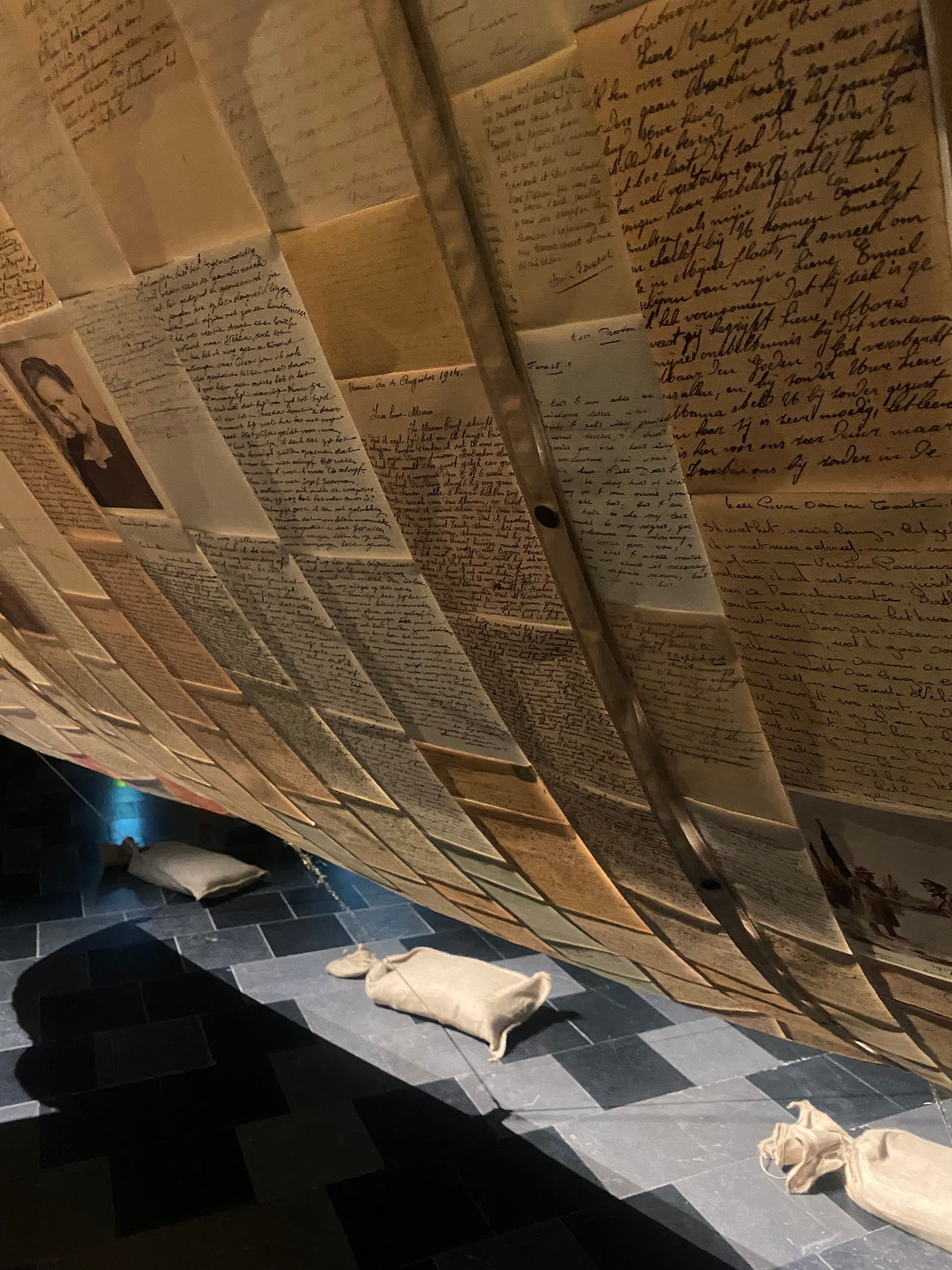

We also went to the 'In Flanders Museum', which was an unforgettable experience. The atmosphere brought the history of World War One to life. The museum was thoughtfully designed with its interactive exhibits. We wandered through displays filled with artefacts, letters and photographs that told the stories of soldiers and civilians impacted by the war. The emotional letters of family members writing to their sons, brothers and husbands made us feel a deep sense of respect and gratitude for those who lived through such challenging times. It was one of the highlights of the day.

We also went to the 'In Flanders Museum', which was an unforgettable experience. The atmosphere brought the history of World War One to life. The museum was thoughtfully designed with its interactive exhibits. We wandered through displays filled with artefacts, letters and photographs that told the stories of soldiers and civilians impacted by the war. The emotional letters of family members writing to their sons, brothers and husbands made us feel a deep sense of respect and gratitude for those who lived through such challenging times. It was one of the highlights of the day.

Having spent some time in Ypres, another part of our visit was to Langemarck Cemetery, where over 44,000 German soldiers were buried. We were particularly struck by the mass grave where so many soldiers had been buried without being identified or individually commemorated.

After this we travelled to Tyne Cot cemetery, which is the largest site in the world commemorating Commonwealth soldiers. This cemetery was much larger than Langemark and all gravestones were the same regardless of rank - reminding us that everyone made the same sacrifice for the war.

After this we travelled to Tyne Cot cemetery, which is the largest site in the world commemorating Commonwealth soldiers. This cemetery was much larger than Langemark and all gravestones were the same regardless of rank - reminding us that everyone made the same sacrifice for the war.

Finally, we explored a section of restored trenches at Sanctuary Wood. Craters from shells that were all around gave us a surreal reminder of the experience of battle. The trenches were also very cramped, which demonstrated just how difficult the living conditions were.

Later, we returned home tired but with a much greater understanding of the realities of the First World War. Thank you to all the teachers who accompanied us and made our trip possible.

Victoria Lawani and Freya Savage, Year 9

The Christmas Truce which occurred during the First World War in 1914 was a unique event in the conflict in which British and German soldiers fighting against one another in the trenches of the Western Front in France and Belgium laid down their guns on Christmas Eve and Christmas Day with some of them exchanging gifts with one another singing carols and even in some instances playing football. Before December 1914, the war on the Western Front had been raging since August, although by the middle of September it had developed into “stalemate” along lines of trenches facing each other with “no man’s land” dividing them and the British and Germans suffering heavy casualties as a result of machine gun fire and the use of heavy artillery weapons. The view that the war would “all be over by Christmas”, which was a common belief on both sides during August and September and which had led to so many men following the call to join the armed forces made by their governments, had now disappeared.

By Christmas, the soldiers on both sides were exhausted and weary of the constant warfare, with many of them having signed up in the early months & being excited by the opportunity to serve their country but now wanting to return home to their families and leave the damp and cold trenches where there was constantly the threat of having to go “over the top” into no man’s land and face almost certain death from enemy fire. The truce was spontaneous, and it began with German soldiers beginning to decorate their trenches with simple Christmas trees and to light candles and sing carols, and there were even some reports that the Germans began to shout across no man’s land, wishing the English “Merry Christmas” in broken English, and although British troops were initially hesitant they eventually began to sing Christmas carols in response being swept along by the mood of the Germans and thinking of loved ones back at home.

By Christmas, the soldiers on both sides were exhausted and weary of the constant warfare, with many of them having signed up in the early months & being excited by the opportunity to serve their country but now wanting to return home to their families and leave the damp and cold trenches where there was constantly the threat of having to go “over the top” into no man’s land and face almost certain death from enemy fire. The truce was spontaneous, and it began with German soldiers beginning to decorate their trenches with simple Christmas trees and to light candles and sing carols, and there were even some reports that the Germans began to shout across no man’s land, wishing the English “Merry Christmas” in broken English, and although British troops were initially hesitant they eventually began to sing Christmas carols in response being swept along by the mood of the Germans and thinking of loved ones back at home.

On Christmas Eve itself, unbelievably, soldiers from both sides along sections of the front line began to get out of the trenches & cross into no man’s land, which was an incredibly brave course of action with enemy machine guns facing them, which could have opened fire at any moment but which, at this time, did not take place leading to more fraternisation between individuals on both sides. Once the soldiers were out in no-man’s land, they exchanged greetings with one another even though in many cases they could understand each other very well and there have been reports that they shook hands and shared some of their food rations and cigarettes with the British giving the Germans some Christmas pudding and the Germans offering cigars and schnapps. There were even instances of showing each other pictures of their wives and children which they kept with them, indicating that although they were from different countries they had a great deal in common which united them.

Possibly the most famous part of the Christmas Truce were the football matches that some soldiers played in no man’s land, with there being several of these taking place in different parts of the frontline, with many of these being spontaneous, informal and quiet short rather than being organised, but they were a reflection of the shared humanity between men from different countries who wanted to put to one side the horrors of war. One German soldier later recalled the events, stating “I remember the silence, the sudden quiet of the guns and the singing. The next day, we were out there walking and talking with the Germans and some of us played football in no man’s land. It was strange, really, to have a game of football with men who only the day before had been trying to kill us”.

It is important to remember, however, that the truce was not universal along the whole of the front line and there were still areas along the front where fighting continued with commanding officers on both sides concerned that the truce would undermine their authority and the morale of the soldiers fighting in the war, and they were quite anxious that it should be brought to an end as quickly as possible. The truce where it took place did not last for a long time and in most cases, within one or two days it came to an end with soldiers being forced back into their trenches and fighting on the front line resuming. It did, however, have a lasting impact and for those soldiers who were involved it proved to be a very emotional experience as it raised questions about the futility of war & what they were fighting for, which became stronger as time passed.

It is important to remember, however, that the truce was not universal along the whole of the front line and there were still areas along the front where fighting continued with commanding officers on both sides concerned that the truce would undermine their authority and the morale of the soldiers fighting in the war, and they were quite anxious that it should be brought to an end as quickly as possible. The truce where it took place did not last for a long time and in most cases, within one or two days it came to an end with soldiers being forced back into their trenches and fighting on the front line resuming. It did, however, have a lasting impact and for those soldiers who were involved it proved to be a very emotional experience as it raised questions about the futility of war & what they were fighting for, which became stronger as time passed.

There would be no repeat of the Christmas Truce in 1915, 1916 and 1917 as commanding officers in both the British and German armies were more prepared for such occurrences in subsequent years, with soldiers being ordered not to fraternise with the enemy even on 25th December. By the end of the war, the events of 1914 seemed a very distant event, although to those soldiers involved it would never be forgotten. In spite of the Christmas Truce of 1914, which happened 110 years ago, this event, or rather, series of events, has created a lasting consciousness amongst many people, demonstrating the potential for kindness, understanding and hope even in the most difficult circumstances. Even though it was not sustained beyond one or two days and did not prevent the resumption of the conflict which would last for nearly another four years, it is still important that it is still remembered because of the values it represented at the time and which remain relevant to us today.

Mr Goodall, Head of History and Politics

On the 21st of September, eight pupils from Years 8 and 9 went to the SPGS Women's Open at St Paul's Girls' School in Hammersmith. Participating in a debate competition provided pupils with an enriching and dynamic experience, offering them the opportunity to hone valuable skills like critical thinking, public speaking, and try using the British Parliamentary debate style. As they prepared for their debates, pupils dived deep into complex topics, learning to analyse multiple perspectives, develop coherent arguments, and counter opposing viewpoints with rebuttals. Throughout the process, they improved their communication skills, becoming more articulate and persuasive speakers. Beyond the academic and intellectual growth, students found the debate environment exciting and enjoyable. They relished the chance to engage in passionate discussions with peers who shared their enthusiasm for tackling important issues. The competitive nature of the events added a thrill, as they strived to outperform their opponents while upholding the principles of respectful discourse. The pupils did a fantastic job, with Amelia Younis-Jourdan and Zoe Chown placing first in the round. Additionally, Mar Costa-Mazmanoglu, Evelyn Sabin, Mia Forster and Eva Estaugh placed second in one round as well!

Student quotes:

Please click on the link here for an inspirational Women's History Month calendar for March.

Cinderella is Dead by Kallyn Bayron

It’s 200 years after Cinderella found her prince, but the fairy tale is over. Teen girls are now required to appear at the Annual Ball, where the men of the kingdom select wives based on a girl’s display of finery.

Sixteen-year-old Sophia would much rather marry Erin, her childhood best friend, than parade in front of suitors. At the ball, Sophia makes the desperate decision to flee, and finds herself hiding in Cinderella’s mausoleum. There, she meets Constance, the last known descendant of Cinderella and her step-sisters. Together they vow to bring down the king once and for all.

This Book is Feminist by Jamia Wilson and Aurelia Durand

'This Book Is Feminist' is a vibrantly illustrated introduction to intersectional feminism for pre-teens and teens.

Discover the history and meaning of the feminist movement through 15 reasons why feminism improves life for everyone.

My Brothers Have Not Read Little Women

My Brothers Have Not Read Little Women

by Scarlett Curtis

We sailed to Treasure Island,

Became Lord of the Flies,

We saw ourselves in Holden C,

Damaged, sad and wise.

We gave our time to Oliver.

Our hearts to Spider-man.

Followed Charlie to the factory,

Took flight with Peter Pan.

Your words are universal.

Your characters are true.

Your stories transcend gender,

But women write books too.

Moxie - Netflix

Moxie - Netflix

Vivian Carter is fed up. Fed up with her small-town Texas high school, who thinks the football team can do no wrong.

Fed up with sexist dress codes and hallway harassment. But most of all, Viv Carter is fed up with always following the rules.

Please click here for further reading materials and other useful links.

When we commemorate those who lost their lives in the First World War and other conflicts over the course of the 20th century on 11th November at 11.00am (the time when this conflict came to an end), this has come to be a moment when we reflect upon the nine million soldiers and seven million civilians who died in the “Great War” of 1914 to 1918. When stories of heroism are mentioned, most focus on the brave men who fought in the trenches.

Women were not allowed in military service at this time and their contributions and experiences in the conflict, whether in terms of working in munitions factories, helping wounded soldiers or taking an active part in other aspects of war work, has often been neglected.

Women were not allowed in military service at this time and their contributions and experiences in the conflict, whether in terms of working in munitions factories, helping wounded soldiers or taking an active part in other aspects of war work, has often been neglected.

Born in 1893, Vera Brittain in Newcastle-under-Lyme in Staffordshire would have a distinguished career as a writer and feminist during the 20th century, with her ideas and beliefs being very much shaped by the experiences she had as a young woman during World War I which she wrote about in “Testament of Youth”.

Born in 1893, Vera Brittain in Newcastle-under-Lyme in Staffordshire would have a distinguished career as a writer and feminist during the 20th century, with her ideas and beliefs being very much shaped by the experiences she had as a young woman during World War I which she wrote about in “Testament of Youth”.

Vera Brittain came from a comfortable background, growing up with younger brother Edward in Macclesfield and Buxton before attending boarding school in Surrey from the age of 13, where she did very well & wanted to continue with her studies at university, although this was opposed by her parents for two years. In 1914, Vera was finally allowed to go to university, becoming an undergraduate at Somerville College, Oxford, where she read English Literature, although to Vera this came to be seen as not being a priority over the course of 1914 to 1915 with the outbreak of World War I and the enlistment of her male contemporaries.

In 1915, Vera took the decision to delay her studies to work as a Voluntary Aid Detachment nurse, which was disapproved of by her parents in the same way as her desire to go to university had been and, over the course of the next three years, she served in hospitals in Buxton, London, Malta, and France. Part of the reason for Vera deciding to leave Oxford and join the VAD was the fact that her younger brother Edward had enlisted in the armed forces along with his friends from school, Roland Leighton (to whom Vera became engaged), Victor Richardson and Geoffrey Thurlow, all of whom she developed close emotional ties.

In 1915, Vera took the decision to delay her studies to work as a Voluntary Aid Detachment nurse, which was disapproved of by her parents in the same way as her desire to go to university had been and, over the course of the next three years, she served in hospitals in Buxton, London, Malta, and France. Part of the reason for Vera deciding to leave Oxford and join the VAD was the fact that her younger brother Edward had enlisted in the armed forces along with his friends from school, Roland Leighton (to whom Vera became engaged), Victor Richardson and Geoffrey Thurlow, all of whom she developed close emotional ties.

Tragically, in December 1915, Roland Leighton was killed by snipers on the Western Front while attempting to repair barbed wire on the front line in France and, as a strategy of dealing with her grief, Vera concentrated on her work as a nurse and helping wounded soldiers, especially as her brother Edward was going to France. Over the course of 1916, Vera kept in touch with her brother Edward, who was injured at the Battle of the Somme, and Victor Richardson and Geoffrey Thurlow, who were also injured out of the conflict, before Thurlow died in military action in April 1917 and Richardson as a result of his injuries in June of the same year.

Tragically, in December 1915, Roland Leighton was killed by snipers on the Western Front while attempting to repair barbed wire on the front line in France and, as a strategy of dealing with her grief, Vera concentrated on her work as a nurse and helping wounded soldiers, especially as her brother Edward was going to France. Over the course of 1916, Vera kept in touch with her brother Edward, who was injured at the Battle of the Somme, and Victor Richardson and Geoffrey Thurlow, who were also injured out of the conflict, before Thurlow died in military action in April 1917 and Richardson as a result of his injuries in June of the same year.

During all of this time, Vera continued to serve with the VAD, being stationed in France and Malta, keeping in touch with brother Edward on a regular basis through letters, particularly as he was moved from the Western Front in France after the battle of Ypres (Passchendaele), to the Italian Front. In June 1918, Edward Brittain led his men on a counterattack against enemy Austrian forces on the front line after suffering heavy bombardment, but was shot through the head by a sniper & died instantaneously after having survived so many other attacks in the war.

During all of this time, Vera continued to serve with the VAD, being stationed in France and Malta, keeping in touch with brother Edward on a regular basis through letters, particularly as he was moved from the Western Front in France after the battle of Ypres (Passchendaele), to the Italian Front. In June 1918, Edward Brittain led his men on a counterattack against enemy Austrian forces on the front line after suffering heavy bombardment, but was shot through the head by a sniper & died instantaneously after having survived so many other attacks in the war.

As a result of her experiences as a nurse in the Voluntary Aid Detachment & the deaths of her brother, fiancé and two close associates (Edward, Roland, Victor, and Geoffrey), Vera became a committed pacifist following the end of the war in 1918, writing up her experiences of this time in “Testament of Youth”. After the war, Vera returned to Oxford to complete her studies and, although she switched from English Literature to History, she went on to become an acclaimed writer, although the poem “Perhaps” which she wrote following the death of Roland Leighton in 1915 & dedicated to him remains a powerful epitaph to all loss in war.

As a result of her experiences as a nurse in the Voluntary Aid Detachment & the deaths of her brother, fiancé and two close associates (Edward, Roland, Victor, and Geoffrey), Vera became a committed pacifist following the end of the war in 1918, writing up her experiences of this time in “Testament of Youth”. After the war, Vera returned to Oxford to complete her studies and, although she switched from English Literature to History, she went on to become an acclaimed writer, although the poem “Perhaps” which she wrote following the death of Roland Leighton in 1915 & dedicated to him remains a powerful epitaph to all loss in war.

Although Brittain did get married and have children during the 1920s, it is widely believed that the tragedies of the deaths of Roland Leighton, Edward Brittain, Victor Richardson and Geoffrey Thurlow remained with her all her life until her death in 1970, especially the death of Roland Leighton as indicated in “Perhaps”.

Although Brittain did get married and have children during the 1920s, it is widely believed that the tragedies of the deaths of Roland Leighton, Edward Brittain, Victor Richardson and Geoffrey Thurlow remained with her all her life until her death in 1970, especially the death of Roland Leighton as indicated in “Perhaps”.

“Perhaps some day the sun will shine again,

And I shall see that still the skies are blue.

And feel once more I do not live in vain,

Although bereft of You.

Perhaps the golden meadows at my feet

Will make the sunny hours of Spring seem gay.

And I shall find the white May blossoms sweet,

Though You have passed away.

Perhaps the summer woods will shimmer bright,

And crimson roses once again be fair,

And autumn harvest fields a rich delight,

Although You are not there.

Perhaps some day I shall not shrink in pain

To see the passing of the dying year,

And listen to Christmas songs again,

Although You cannot hear.

But, though kind Time may many joys renew,

There is one greatest joy I shall not know

Again, because my heart for loss of You

Was broken, long ago.”

Eliza “Elsie” Inglis was born in 1864 in India, which at the time formed part of the British Empire, where her father was a magistrate who worked for the Indian Civil Service and, over the course of her life, would qualify as a doctor and become a medical surgeon, both of which were highly unusual for women at this time.

Eliza “Elsie” Inglis was born in 1864 in India, which at the time formed part of the British Empire, where her father was a magistrate who worked for the Indian Civil Service and, over the course of her life, would qualify as a doctor and become a medical surgeon, both of which were highly unusual for women at this time.

On the retirement of her father from the Indian Civil Service, Elsie returned to Britain, settling in Scotland, which was the home of the family, and in 1887, following the completion of her formal education, she started her studies at the Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women opened by Dr Sophia Jex-Blake. After her graduation in 1892, Elsie gained a job at the New Hospital for Women in London, set up by Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, before returning to Edinburgh in 1894 to work in several medical institutions in the city during the period up to the outbreak of the First World War in 1914.

Although Elsie was over 50 by the time the conflict started, this would be the part of her life to which she would make the greatest contribution, setting up the Scottish Women’s Hospitals for Foreign Service Commission to provide medical support for the British Armed Forces fighting in Europe. In spite of considerable opposition and a lack of financial support from the British authorities, Inglis was able to send 14 all-female teams of doctors, nurses and technical support teams to Belgium, France, Serbia and Russia, which was very remarkable after originally being told “my good lady go home and sit still”.

Although Elsie was over 50 by the time the conflict started, this would be the part of her life to which she would make the greatest contribution, setting up the Scottish Women’s Hospitals for Foreign Service Commission to provide medical support for the British Armed Forces fighting in Europe. In spite of considerable opposition and a lack of financial support from the British authorities, Inglis was able to send 14 all-female teams of doctors, nurses and technical support teams to Belgium, France, Serbia and Russia, which was very remarkable after originally being told “my good lady go home and sit still”.

Elsie herself went to support the war on the Serbian Front in Southeastern Europe, working to improve hygiene amongst the soldiers, resulting in outbreaks of typhus and other epidemics being reduced significantly, although she was captured by German and Austrian forces and repatriated to Britain in 1916. The experiences Elsie faced in Serbia did not deter her from entering conflict zones and, in the same year, headed for the Russian Front in Eastern Europe and set up a hospital at Braila in Romania in which just 7 doctors, including herself, came to be responsible for treating 11,000 wounded soldiers and sailors.

Elsie herself went to support the war on the Serbian Front in Southeastern Europe, working to improve hygiene amongst the soldiers, resulting in outbreaks of typhus and other epidemics being reduced significantly, although she was captured by German and Austrian forces and repatriated to Britain in 1916. The experiences Elsie faced in Serbia did not deter her from entering conflict zones and, in the same year, headed for the Russian Front in Eastern Europe and set up a hospital at Braila in Romania in which just 7 doctors, including herself, came to be responsible for treating 11,000 wounded soldiers and sailors.

In 1917 Elsie was forced to return to Britain, having contracted bowel cancer and died shortly after arriving back in the country, although by this time her efforts in the war had been recognised by politicians in Britain and Serbia and in the latter she became the first woman to hold the Serbian Order of the White Eagle. After the death of Inglis in 1917 a memorial fountain was constructed in the town of Mladenovac in Serbia where her hospital had been set up during World War I and had helped save the lives of many Serbian soldiers fighting for the Allies against Germany and Austria in the conflict.

In 1917 Elsie was forced to return to Britain, having contracted bowel cancer and died shortly after arriving back in the country, although by this time her efforts in the war had been recognised by politicians in Britain and Serbia and in the latter she became the first woman to hold the Serbian Order of the White Eagle. After the death of Inglis in 1917 a memorial fountain was constructed in the town of Mladenovac in Serbia where her hospital had been set up during World War I and had helped save the lives of many Serbian soldiers fighting for the Allies against Germany and Austria in the conflict.

Flora Sandes was born in 1876 and, during her early life, enjoyed various outdoor pursuits such as riding and shooting and even learned to drive a car during the first decade of the 20th century, with all of these activities being against conventions at the time and what women were expected to do with their time.

After she had completed her formal education at school, Flora trained with the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (FANY), which was founded in 1907 as an all-women mounted paramilitary organisation in which its members learned first aid as well as horsemanship, together with military aspects such as signalling and drill. In 1910, Flora left the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry and helped establish a new organisation called the Women’s Sick and Wounded Convoy Corps with its purpose being to assist soldiers in war zones, and in 1912 it saw service in Bulgaria and Serbia during the First Balkan War.

After she had completed her formal education at school, Flora trained with the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (FANY), which was founded in 1907 as an all-women mounted paramilitary organisation in which its members learned first aid as well as horsemanship, together with military aspects such as signalling and drill. In 1910, Flora left the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry and helped establish a new organisation called the Women’s Sick and Wounded Convoy Corps with its purpose being to assist soldiers in war zones, and in 1912 it saw service in Bulgaria and Serbia during the First Balkan War.

With the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, Flora volunteered to become a nurse, but she was rejected because of a lack of qualifications and instead joined a St John Ambulance unit and left Britain for Serbia on 12th August with 36 women to try and assist the crisis which had developed in this part of the war. On arriving at Kragujevac in Serbia, which was a base for the Serbian army which was attempting to prevent the Austrian army from conquering the country, Flora joined the Serbian Red Cross and became a nurse and ambulance driver providing medical assistance to injured soldiers in the conflict.

With the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, Flora volunteered to become a nurse, but she was rejected because of a lack of qualifications and instead joined a St John Ambulance unit and left Britain for Serbia on 12th August with 36 women to try and assist the crisis which had developed in this part of the war. On arriving at Kragujevac in Serbia, which was a base for the Serbian army which was attempting to prevent the Austrian army from conquering the country, Flora joined the Serbian Red Cross and became a nurse and ambulance driver providing medical assistance to injured soldiers in the conflict.

Inspired by some of the Serbian soldiers whom she met, it was suggested to her by them that she was wasted as a nurse and that she should enlist as a soldier and during the course of 1915 she attempted to get to the front line and eventually joined the ambulance of the Second Serbian Regiment at Babuna Pass. Following a Serbian retreat through Albania as a result of an Austrian offensive, all the other ambulance staff either fled or were killed and, as Flora could no longer make herself useful as a nurse, she was enrolled as a private in the Serbian army and before long proved herself effective, being promoted to corporal.

Inspired by some of the Serbian soldiers whom she met, it was suggested to her by them that she was wasted as a nurse and that she should enlist as a soldier and during the course of 1915 she attempted to get to the front line and eventually joined the ambulance of the Second Serbian Regiment at Babuna Pass. Following a Serbian retreat through Albania as a result of an Austrian offensive, all the other ambulance staff either fled or were killed and, as Flora could no longer make herself useful as a nurse, she was enrolled as a private in the Serbian army and before long proved herself effective, being promoted to corporal.

In 1916, Flora was seriously wounded by a grenade during a Serbian attack after displaying considerable bravery for which she was rewarded with the Order of the Karadorde’s Star, which was the highest decoration of the Serbian military, and was promoted to the rank of sergeant major, receiving a number of medals. As Flora was unable to fight, she wrote her autobiography on her experiences and helped raise funds for the Serbian Army as well as running a hospital for injured Serbian soldiers, and after the war, a law was passed in Serbia making Flora Sandes the first female commissioned officer in the army.

In 1916, Flora was seriously wounded by a grenade during a Serbian attack after displaying considerable bravery for which she was rewarded with the Order of the Karadorde’s Star, which was the highest decoration of the Serbian military, and was promoted to the rank of sergeant major, receiving a number of medals. As Flora was unable to fight, she wrote her autobiography on her experiences and helped raise funds for the Serbian Army as well as running a hospital for injured Serbian soldiers, and after the war, a law was passed in Serbia making Flora Sandes the first female commissioned officer in the army.

After the war, Flora married a Russian émigré from the Revolution of 1917 and the couple lived in France for a time before returning to Serbia, which was now part of the new country of Yugoslavia, although after the death of her husband in 1941, Flora returned to live in Britain, where she died in 1956. Flora Sandes is unique in the sense that she remains the only British woman to officially serve as a soldier during the First World War, breaking all the rules and protocols of the time regarding the role of women in society and in conflict and successfully challenging the British government, which did not want her to serve.

After the war, Flora married a Russian émigré from the Revolution of 1917 and the couple lived in France for a time before returning to Serbia, which was now part of the new country of Yugoslavia, although after the death of her husband in 1941, Flora returned to live in Britain, where she died in 1956. Flora Sandes is unique in the sense that she remains the only British woman to officially serve as a soldier during the First World War, breaking all the rules and protocols of the time regarding the role of women in society and in conflict and successfully challenging the British government, which did not want her to serve.

Mr Goodall, Head of History

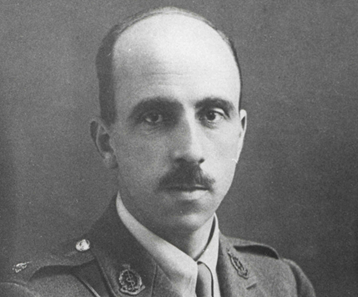

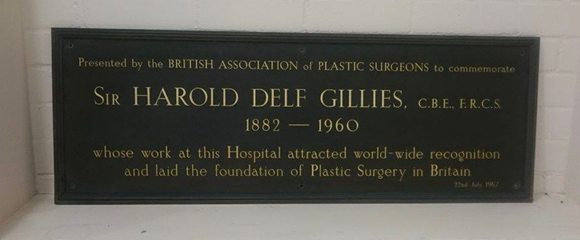

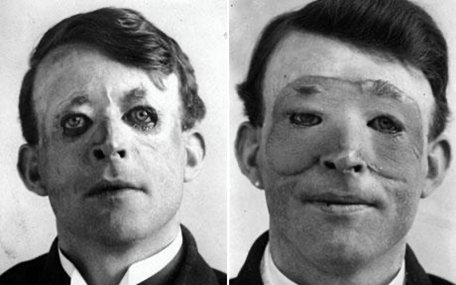

Harold Gillies:

Harold Gillies: It was during his time in France that Gillies was introduced to the ever-increasing severity of facial wounds sustained by those fighting in the War: an increase indubitably a result of the emergence of new forms of weaponry.

It was during his time in France that Gillies was introduced to the ever-increasing severity of facial wounds sustained by those fighting in the War: an increase indubitably a result of the emergence of new forms of weaponry. The Queen’s Hospital

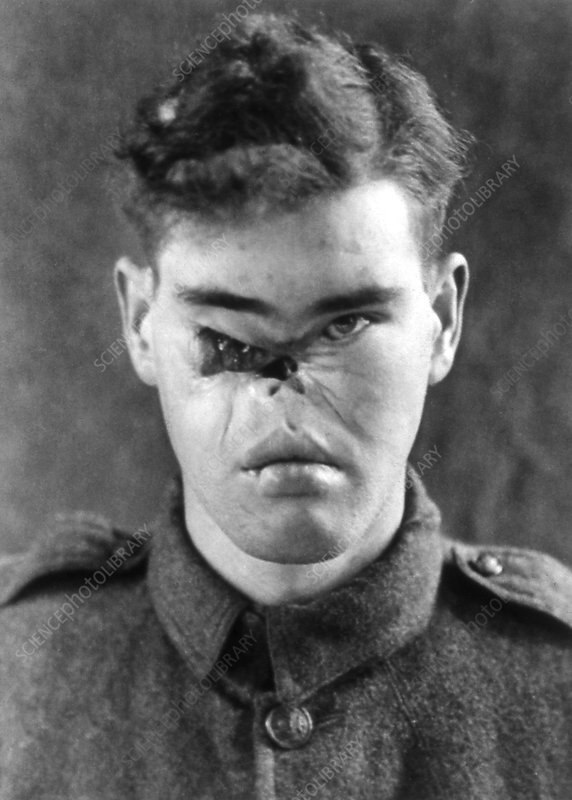

The Queen’s Hospital Usually, most skin grafts involve taking a flap of skin elsewhere (known as a “Pedicle”) and wrapping it around the wound without severing the flap’s connection to the body. This traditional technique was successfully performed in 1917 on Walter Yeo (right), a naval officer who had lost both eyelids in 1916 at the Battle of Jutland.

Usually, most skin grafts involve taking a flap of skin elsewhere (known as a “Pedicle”) and wrapping it around the wound without severing the flap’s connection to the body. This traditional technique was successfully performed in 1917 on Walter Yeo (right), a naval officer who had lost both eyelids in 1916 at the Battle of Jutland.

Dubbed the ‘Father of Plastic Surgery’ for his groundbreaking techniques, Gillies revolutionised the way in which plastic surgery was perceived and used for centuries to come - with many of the reconstructive techniques that he began to implement (such as his “Tubed Pedicle”) serving as the foundation for modern plastic surgery as we know it. His attempts at providing those gallant men who accrued life-altering injuries extended far beyond the surgical room, even introducing training schemes for his patients, so they could develop new skills, fit to combat the disadvantages they could face in the labour market. Additionally, Gillies’ endeavours conceived the concept of “Cosmetic Surgery”, with his admirable focus on restoring a “normal” appearance for veterans, allowing for freedom of choice regarding the features which they were to have transplanted. Yet, above all, Gillies’ commitment to the practice of plastic surgery serves as an ever pertinent reminder of the unwavering commitment of those who sat behind the front lines: whose efforts to improve the lives of those permanently afflicted by the First World War are not just mere pages in history, but a testament to the boundless capacity of a man to make a difference.

River Wattret, Year 12

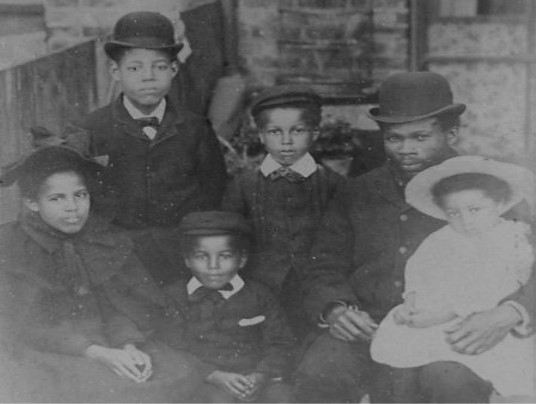

Walter Tull was born in Folkestone Kent in 1888 bein g the grandson of a slave with his father having arrived in the country from Barbados in 1876, although his mother died when he was just 7 years old and Tull & his brother Edward were sent to a Children’s Orphanage in Bethnal Green.

g the grandson of a slave with his father having arrived in the country from Barbados in 1876, although his mother died when he was just 7 years old and Tull & his brother Edward were sent to a Children’s Orphanage in Bethnal Green.

The reason why this decision was taken was because it was believed it would prevent the family from becoming destitute as Tull’s stepmother was struggling to cope with a large family as he had four  other siblings & the two older boys were seen as liabilities that the family could not afford.

other siblings & the two older boys were seen as liabilities that the family could not afford.

At the time Tull and his brother were sent to the orphanage there was always the option that he could return home although in the event the two boys stayed in the institution which was a relatively safe environment until their teenage years and were starting to think of life beyond the home.

Tull completed his education whilst in the orphanage before getting a job at a local printers which he was hoping would provide an opportunity for him to have some kind of career as a reporter on a newspaper & in his spare time he played football on a regular basis as this was a real passion for him.

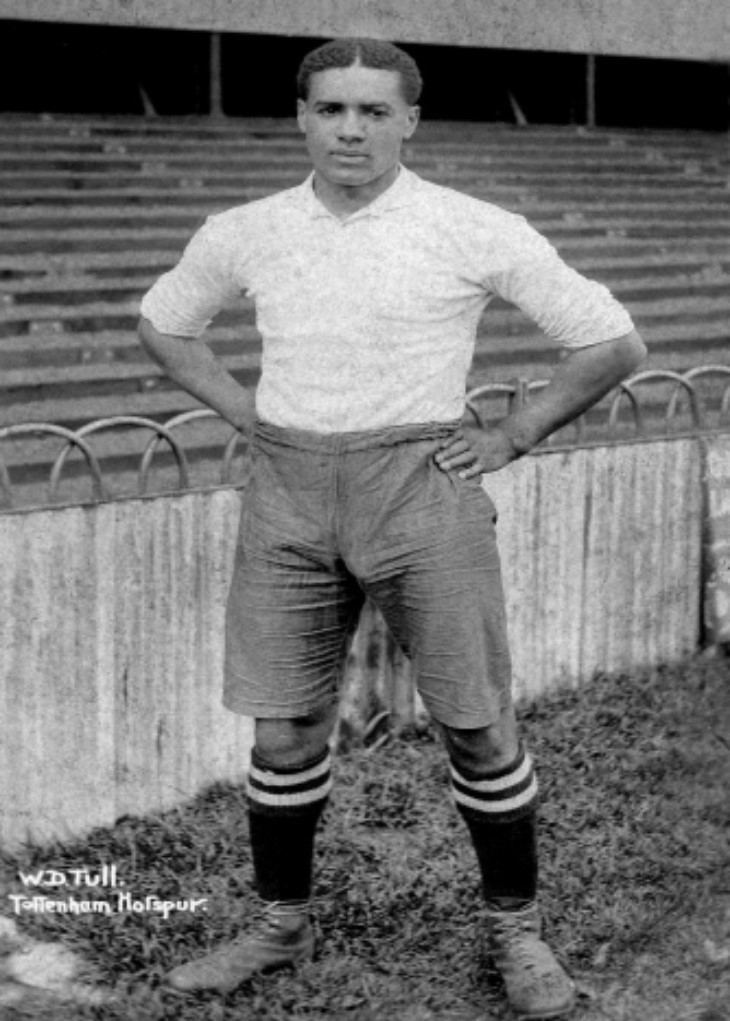

Walter Tull showed himself to be a talen ted footballer and when he was 20 in 1908 he had a trial for local amateur team Clapton in the East End of London and was picked to play for them and after just one season he had made such an impression that he was spotted by talent scouts who were looking for new players and signed up by Tottenham Hotspur from the First Division (top flight of football in Britain at this time) For this he received a signing on fee of £10 and a wage of £4 a week.

ted footballer and when he was 20 in 1908 he had a trial for local amateur team Clapton in the East End of London and was picked to play for them and after just one season he had made such an impression that he was spotted by talent scouts who were looking for new players and signed up by Tottenham Hotspur from the First Division (top flight of football in Britain at this time) For this he received a signing on fee of £10 and a wage of £4 a week.

At this time Tull was the only second black man to play professional football in Britain, and he soon settled in at Tottenham making a significant impression on the club who had just been promoted to the First Division, although he often had to deal with racial abuse from opposition fans at away fixtures.

After just seven games for Tottenham however Tull was dropped and during the following season he joined Northampton Town and played just three games but after this he did become a regular player for the team and began to generate interest in other clubs notably Glasgow Rangers who wanted to sign him.

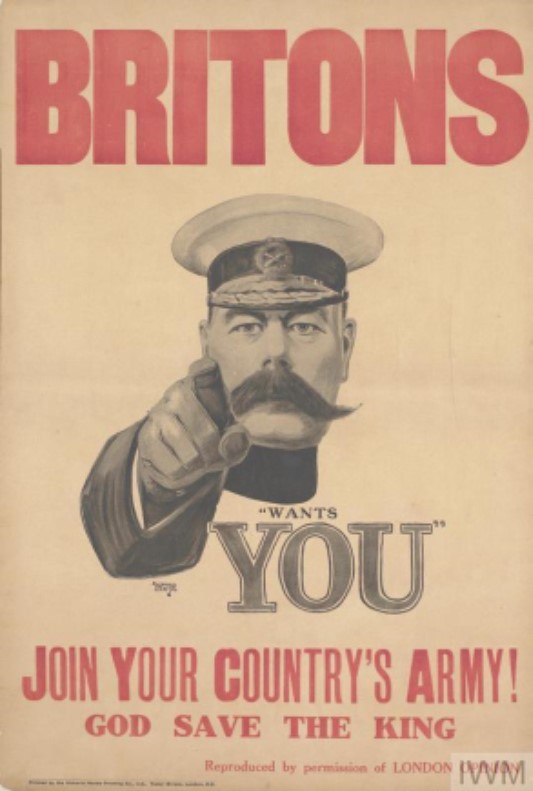

The move of Walter Tull to Rangers never took place because of the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 resulting in his decision to join the army as a member of the Football Battalion and within a relatively short period of time he was promoted to the rank of sergeant indicating his leadership potential.

The move of Walter Tull to Rangers never took place because of the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 resulting in his decision to join the army as a member of the Football Battalion and within a relatively short period of time he was promoted to the rank of sergeant indicating his leadership potential.

Walter Tull was not posted to the Western Front until November 1915 and once here he found the situation in the trenches challenging and suffered from shellshock particularly after being involved at the Battle of the Somme which started in July and was sent home in order to recover from his condition. Within a relatively short period of time Tull returned to the Western Front, but he was sent home again suffering from trench fever although in spite of this he continued to impress his military superiors who recommended that he should be considered for further promotion as an officer.

Walter Tull was sent to the officer training school at Gailes in Scotland and in spite of military regulations which stated that “any negro or person of colour” could not be an officer Tull received his first commission as a Lieutenant in May 1917 and in doing so became the first Black combat officer in the British Army.

Walter Tull was sent to the officer training school at Gailes in Scotland and in spite of military regulations which stated that “any negro or person of colour” could not be an officer Tull received his first commission as a Lieutenant in May 1917 and in doing so became the first Black combat officer in the British Army.

Tull was sent to the Italian Front and led his soldiers at the Battle of Piave in January 1918 and was remarkably successful in his first raid as his battalion suffered no casualties in spite of the fact that they were under intense fire by the enemy with this being viewed as impressive by his superiors. Tull remained in Italy until 1918 when he was transferred to France so as to take part in the attempt to break the German lines on the Western Front and on 25th March he was ordered to lead an attack on their position at Favreuil, but he was shot by German fire in the head in No Man’s Land and died instantly.

During his relatively short period in command Tull had become a popular officer with his men and following his death several of them attempted to rescue his body from No Man’s Land and bring it back to the British trenches but had to give up because of heavy enemy fire from German machine gun positions.

It is now known that Tull was recommended for the Military Cross because of his bravery in battle, although this was never received by his family with the Ministry of Defence claiming that there is no record of such a recommendation existing, although it is now believed that the issue of race played a part.

Mr Goodall, Head of History

Twenty-one million injured. Over nine million soldiers killed. A tragedy forever in our minds.

From 1914 to 1918, Europe was brought to a standstill as World War One (WW1) raged throughout the continent. Over 30 nations declared war and seventy million military personnel were sent to fight for their countries. To honour their heroism, bravery and sacrifice, we have Remembrance Day. Celebrated annually, Remembrance Day is observed throughout the Commonwealth on the 11th of November at 11AM, at the time Germany surrendered to The Allies.

Many soldiers would have been young, encouraged by the omnipresent propaganda and galvanised by the rising patriotism in Britain, to enlist. As students ourselves, it’s imperative to recognise the great number of lives lost at such a young age. Many were young: 17-19 years old. They were barely older than us, yet they were not comfortably learning in school but suffering in the trenches and dying on the battlefield. On the 11th of November, we must remember both the savagery of war that cut their lives short, and celebrate their sacrifices. Further than that, we must remain grateful for the opportunities in life given to us that were not possible for them, and choose to live life to the fullest...

This year, I’m also choosing to highlight those who aren’t always celebrated on Remembrance Day. Soldiers on the battlefield faced great struggles; however, women left on the Homefront also faced problems and overcame them with admirable courage. These issues included food shortages, bomb strikes and a crippled economy. Fear and hardship were rife at home, yet those who suffered are often forgotten on Remembrance Day. Girl Guides picked up shovels and grew food for the whole nation; children knitted socks for soldiers;

This year, I’m also choosing to highlight those who aren’t always celebrated on Remembrance Day. Soldiers on the battlefield faced great struggles; however, women left on the Homefront also faced problems and overcame them with admirable courage. These issues included food shortages, bomb strikes and a crippled economy. Fear and hardship were rife at home, yet those who suffered are often forgotten on Remembrance Day. Girl Guides picked up shovels and grew food for the whole nation; children knitted socks for soldiers; women became farmers, train drivers and factory workers. The bravery they displayed in face of great upheaval should not be forgotten, but celebrated alongside the actions of brave soldiers for their contribution in winning the war.

women became farmers, train drivers and factory workers. The bravery they displayed in face of great upheaval should not be forgotten, but celebrated alongside the actions of brave soldiers for their contribution in winning the war.

Many soldiers were also forgotten; in particular, 1.5 million soldiers from British colonies in Asia and Africa have been erased from history. Rather than being commemorated with headstones, like their comrades, their names were scrawled on a registar, and they were buried in mass graves. We never learn about their bravery, their truth, and they remain forgotten. By choosing to highlight their bravery this Remembrance Day, we do not diminish the actions of British soldiers but instead embrace the strength and courage shown by all those who contributed in World War One, regardless of race and nationality.

their truth, and they remain forgotten. By choosing to highlight their bravery this Remembrance Day, we do not diminish the actions of British soldiers but instead embrace the strength and courage shown by all those who contributed in World War One, regardless of race and nationality.

In the sixty seconds we have on the 11th of November, let us remember all those who contributed to the war effort. Let us remember all the women, all the leaders and all the soldiers who helped secure our future. But most importantly?

Let us take their sense of unity and togetherness forward into the future. In face of recent problems, the world has fractured, and each nation has chosen to pursue its own selfish interests. Countries have chosen to ignore each other's struggles and forced themselves to battle alone. This is not a viable solution. We must step into the future: together and united.

Megan Lisle & Megan Le, Year 12

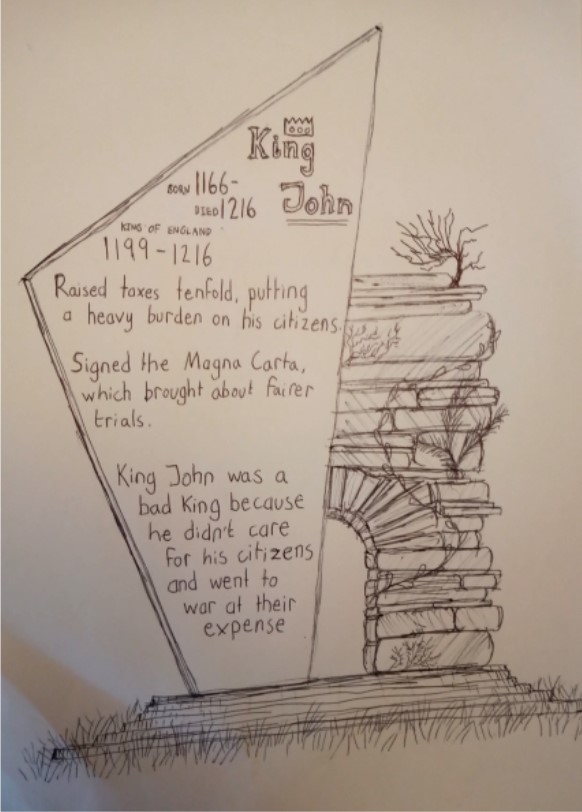

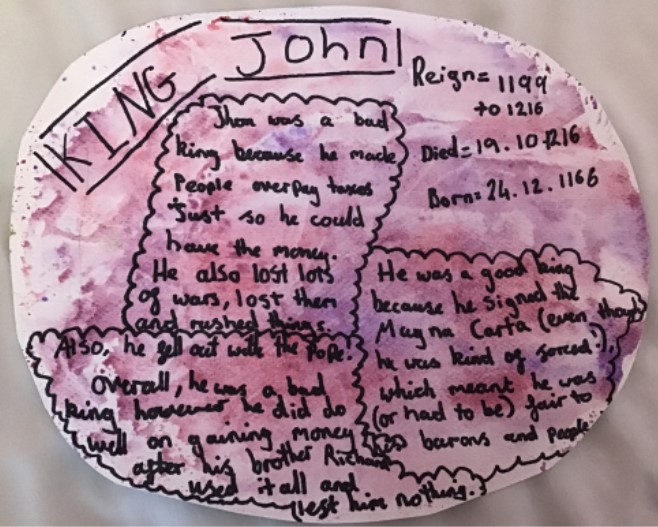

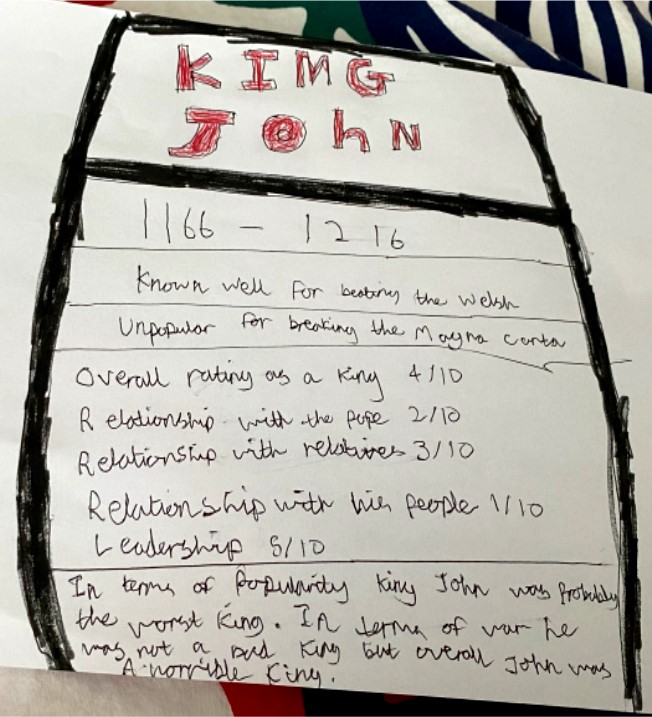

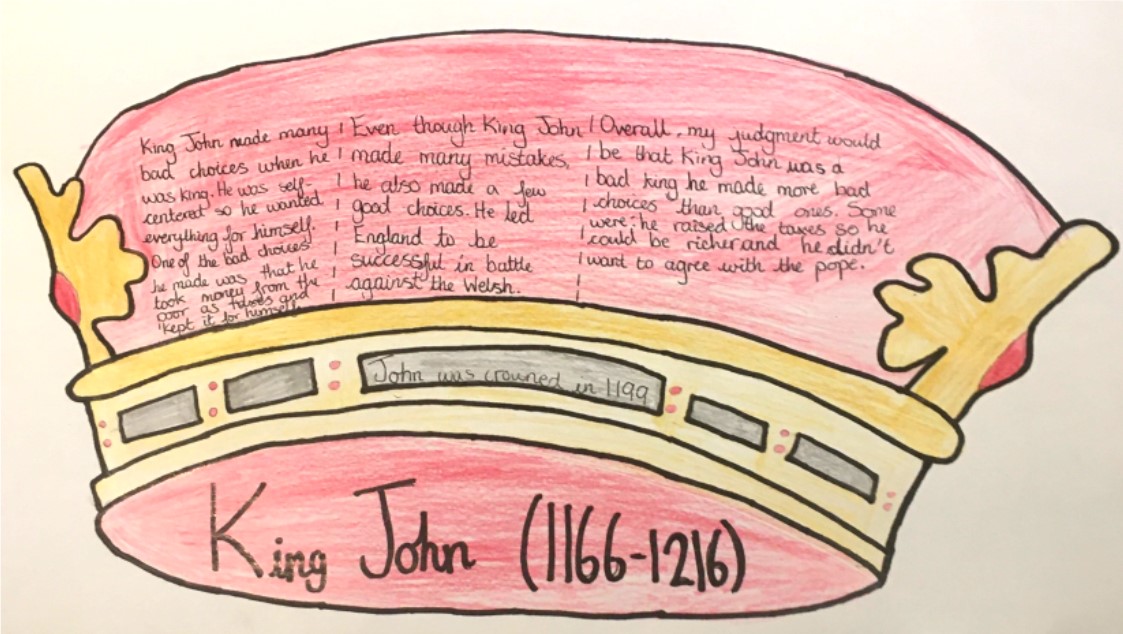

Students in 7CPB have been studying King John and the Magna Carta and have created plaques to commemorate his reign. So many excellent pieces of work, so well done to everyone who submitted their designs. Here are a selection of some of the best efforts.

Mr Martin, History Department

Lev Griffin, Year 7

Layla Evans, Year 7

Jibril Dahir, Year 7

Ayaka Machida, Year 7

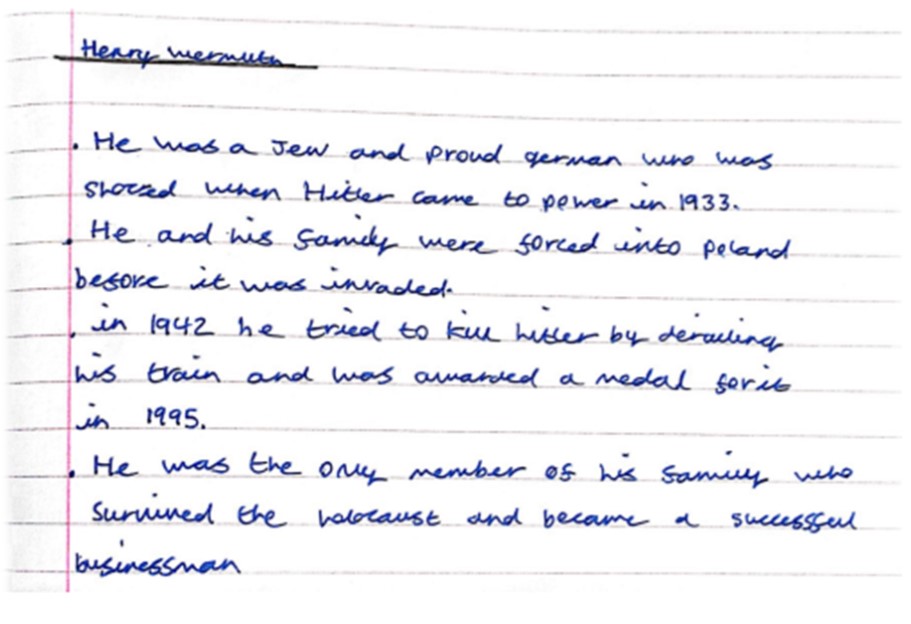

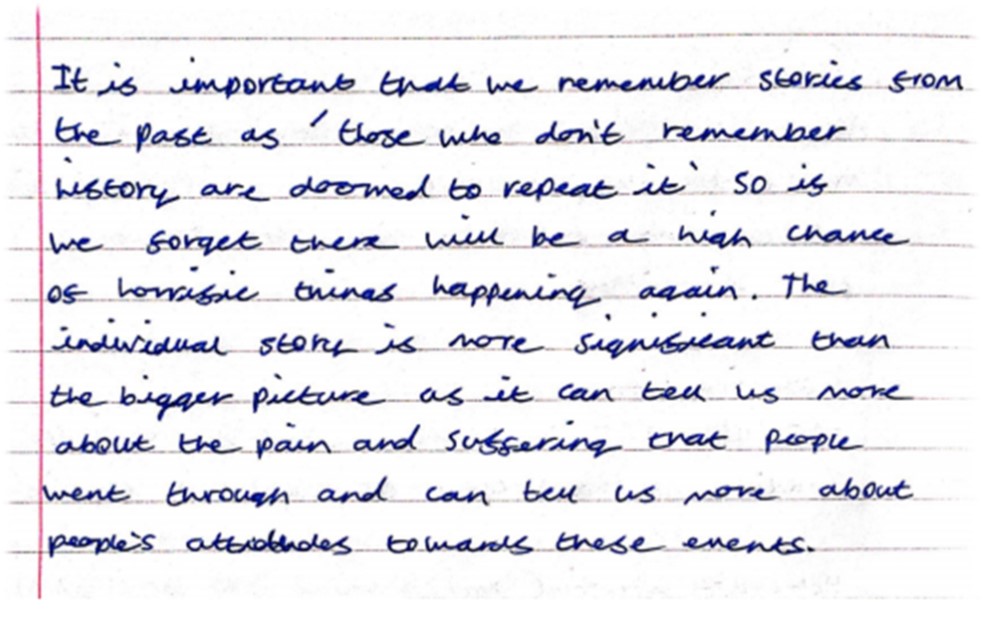

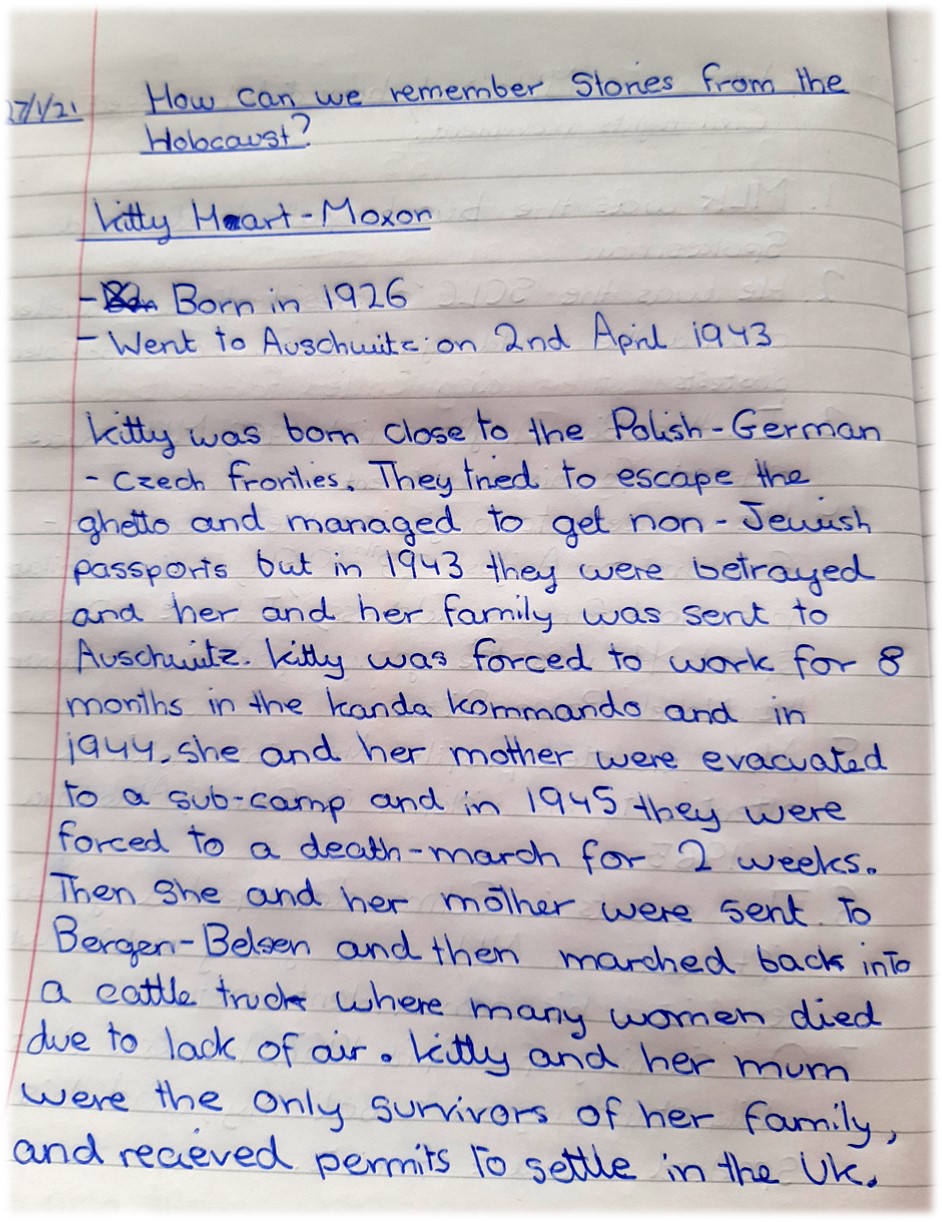

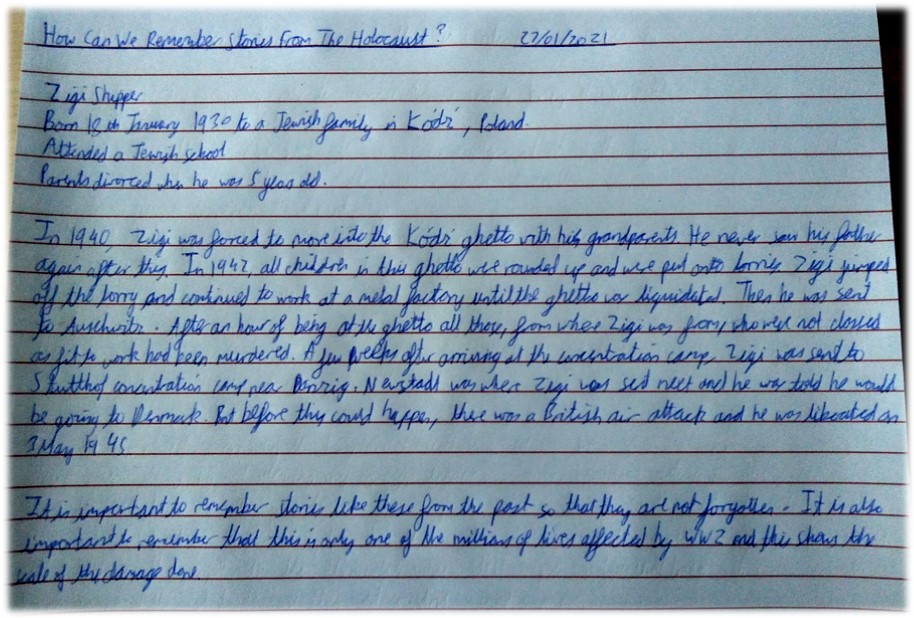

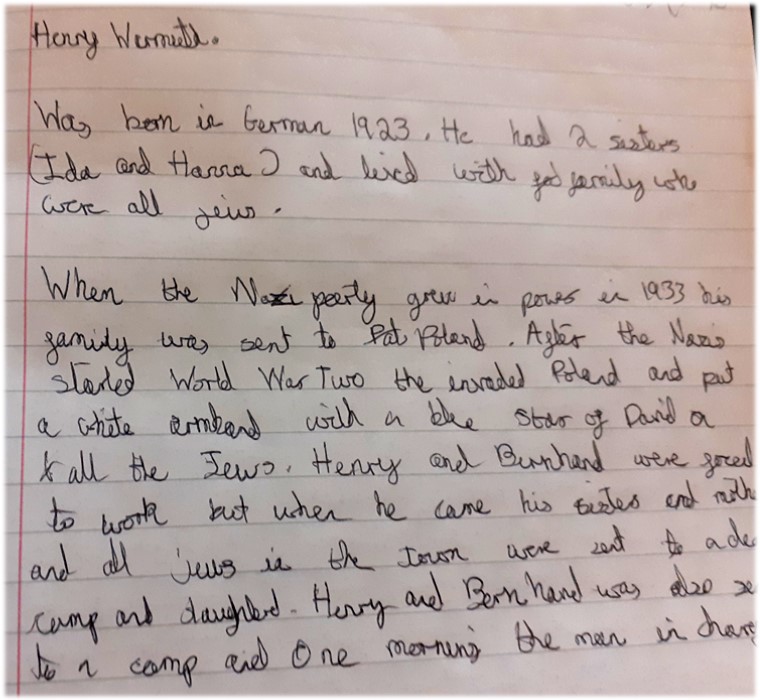

Students at Bexley Grammar School have been learning about the Holocaust this week in line with Holocaust Memorial Day on January 27th. January 27th 1945 was the date that the biggest Nazi concentration camp, Auschwitz-Birkenau, was liberated by Russian troops, bringing to an end the systematic murder of Jewish, Gypsy, LGBT and other people in that part of Poland. The Holocaust claimed the lives of over 6 million people and affected millions more. Students have been learning about the stories of some of the individuals who were affected by the Holocaust in their English, FBCS and History lessons and some of their work is shared below.

Thanks to all the staff who enabled this and delivered the material to students. Thank you to all of the students who participated and contributed their ideas.

Mr Martin, History Teacher

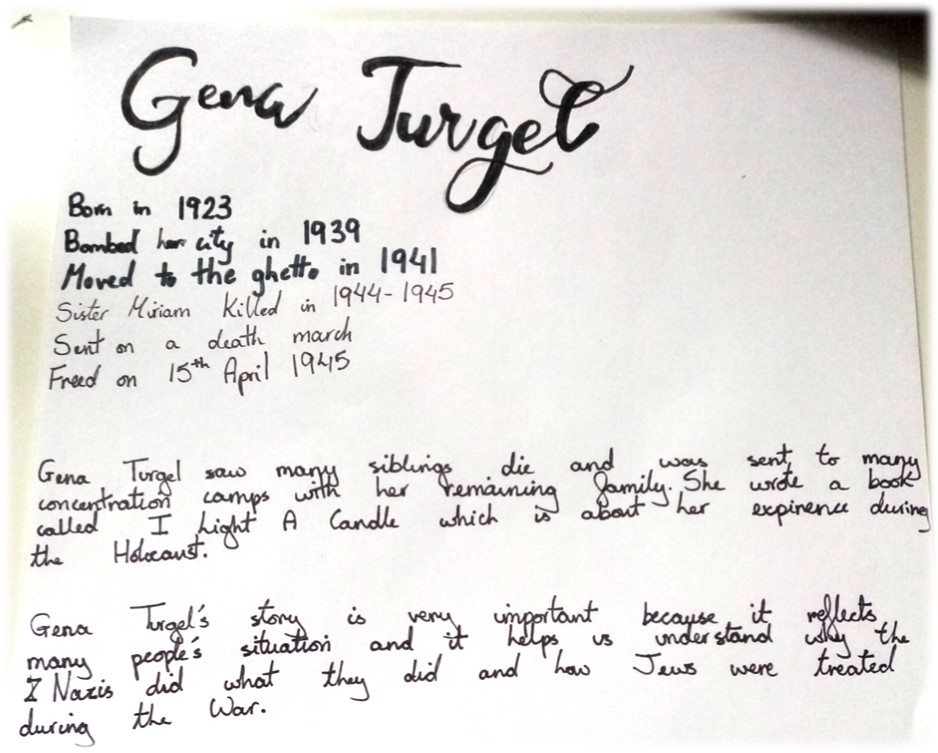

Gena Turget- Birth 1923

1st September 1939- her house was first bombed

Autumn 1941- moved to the ghetto in Krakow

1944-45 sent to Auschwitz

January 1945- sent on trucks to Bergen Belsen

15th April 1945– Bergen Belsen was liberated

Gena was only 16 when her house was bombed at the beginning of the war, which meant she then had to move to a ghetto where some of her family were shot. When they were found they were forced to constantly move from one camp to another until she was finally liberated in 1945, with only her Mother left as her remaining living family.

We need to remember these stories, so it reminds us of this despicable crime and not to do it again. Gena helps us remember that not only adults, but children who were brought up in Judaism were taken to concentration camps too, and that genocide is a despicable crime which should never happen in large or small numbers ever again. From her experiences she has written a book “I light a candle”.

Jessica Davis, Year 7

Aaron Kiley, Year 9

Emilia Morgan, Year 9

Reine Inow

Born: 1929 in Germany

Lived with: her mother, her father, her brother and her sister

Reine Inow was born in Germany and was a Jew. When she was 10 years old, her brother was taken to a concentration camp and she was sent away to Britain by the Kinder transport - a programme that helped children escape Germany to find a safer place to live. She arrived in England and stayed with her aunt. Reine managed to escape the holocaust, however, her parents sadly did not. She still lives in England and has ever since.

It’s important that Reine’s story is remembered because it helps us remember that not all Jews were killed in the Holocaust and that everyone can find hope in anything.

Layla Evans, Year 7

Alice Colaiacomo, Year 7

Hari Rehal, Year 8

Samuel Raji, Year 8

Cookie Policy